Association of Perfectionism with Job Search Behavior and Career Distress among Nursing Students in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Understanding the influence of perfectionism among senior nursing students is imperative for addressing strategies to reduce career distress and enhance job search behavior. The purpose of this study was to identify perfectionism types among senior nursing students in South Korea. Differences in career distress and enhanced job search behavior for each perfectionism type were compared.

Methods

A cross-sectional, descriptive design was employed. A total of 211 nursing students completed surveys for Perfectionism, Job Search Behavior, and Career Distress. Cluster analysis and post-hoc tests were conducted.

Results

A total of 80.1% were classified into the perfectionism group, including adaptive (49.8%) and maladaptive (30.3%). Maladaptive groups showed the highest discrepancy between standards and their perceived achievements as well as career distress. Job search behavior was the highest in the adaptive perfectionism group but the lowest in the non-perfectionism group.

Conclusion

Nursing educators should consider career coaching customized by each perfectionism type to improve job search behavior among nursing students.

INTRODUCTION

As healthcare organizations in many countries suffer from a nursing shortage, the demand for nursing care is ever increasing [1]. The 1-year turnover rate among new graduates in the United States was 19.1%, and an additional one-third leave within two years [2]. In South Korea, approximately 50% of the newly graduated nurses left their first job, among which a half left their first job within a year [3]. Although 77% of the newly employed nurses moved to a new workplace two years after graduation, paradoxically, about 23% of the new graduates have difficulties in finding jobs as nurses [4]. To ultimately resolve the nursing workforce shortage, nursing researchers and educators should consider both the high turnover rate of experienced nurses and the unemployment problem of new graduates. The factors contributing to the staffing shortage and the unemployment of new nurses are complex and vary depending on the country and culture [1]. Among them, Kanfer et al. [5] highlighted that the relationship between antecedents, such as personality traits, and job search behavior determined employment outcomes. Seren et al. [6] also pointed out the importance of providing guidance to nursing students regarding proper career-planning and decision-making before graduating from nursing school because nurses’ job satisfaction is adversely influenced by random choice of work.

Career planning and decisions are critical to personal and professional happiness throughout one’s life [7]. Personal career goals are achieved through active exploration of the profession and actual job search behavior. Job search behavior is part of the self-regulatory process that involves pursuing a career goal [5]. It constitutes all practical and specific career-related actions taken by individuals to make a proper career decision [8], including collecting information about different careers and the self and planning for a future work life [4]. This process increases self-awareness in terms of their future career life and helps adapt as they transition to working life [8]. Job search behavior among nursing students was also found to play an important role in their successful transition as professional nurses [4], leading to higher job satisfaction and lower turnover intention [9].

During job search, individuals attempt to gather information about potential job positions or conditions through formal and informal networks [4,8]. Individuals may also experience career distress such as helplessness, aimlessness, and anxiety that negatively affect them [7]. Career distress during job search process is one of the most common reasons cited among university students who need psychological help [10]. Career distress impeded important behaviors, such as career exploration and planning [7]. Previous studies have reported its relation with career decidedness, career discrepancy, and life satisfaction [8,10]. Mild to severe stress is the first phenomenon that occurs when people search for a job, as individuals realize a career discrepancy between their current situation and the conditions that they should fulfill to get a job [7]. Saber et al. [11] reported that mild career distress positively affects job search behavior. Excessive stress, however, causes a variety of psychological problems that hinders one’s actions toward professional career paths [12].

Previous studies [7,10] recommend career counseling programs to improve job search behavior and reduce career distress, which in turn enhances students’ employment and increases job satisfaction in the future. To establish effective career centers, factors influencing individuals’ job search behavior and career distress should be identified. Kanfer et al.[5] proposed a heuristic model of job search behavior in which personality traits were a significant antecedent of job search behavior. The cognitive diathesis-stress model postulated that the influence of stress on adaptation varies depending on individuals’ internal resources, such as their personality traits [13,14]. Earlier studies have reported that perfectionism as a personality trait is related to career-related variables, such as career choice adjustment, indecision, career adaptability, and career barriers [8,15].

Perfectionism is a personality trait characterized by striving for flawlessness and setting high standards for performance, resulting in overly critical evaluations of one’s behavior [16]. Rice et al. [17] proposed that individuals function with either adaptive or maladaptive perfectionism. Maladaptive perfectionism is negatively associated with self-efficacy in career decision-making and higher perceptions of career barriers [15]. Maladaptive perfectionism may increase students’ doubts about their ability to perform their roles with their current knowledge and skills [16]. Meanwhile, adaptive perfectionism predicted higher job search behavior among secondary school students in Turkey [18]. Adaptive perfectionism also exhibited a positive relationship with career adaptability and career optimism [15]. An increasing number of nurses are becoming more perfectionistic because their professional roles involve dealing with human life [19]. Furthermore, the nursing educational principle of accuracy in performance causes a high tendency toward perfectionism among nursing university student [20]. Therefore, nursing students’ perfectionism may cause individual differences in job search behavior and career distress based on the different appraisals of the job search process.

Several studies [15,18,21] have examined the association between perfectionism and career-related variables in a variety of populations; however, no studies have investigated how perfectionism may be related to job search behavior and career distress among nursing students. Statistically, it has been revealed that a higher proportion of students majoring in medical fields such as nursing, medicine, and ontology exhibit perfectionism than those who do not individual differences affect employment success [5,20,22]. A better understanding is needed of the impact of perfectionism based on individual differences on nursing students’ behaviors and stress. In addition, studies on perfectionism subtypes among nursing students remain limited. To identify the individual factors contributing to job search behavior and career distress, this study aims to compare the differences in job search behavior and career distress by different perfectionism types after identifying the perfectionism subtypes of nursing university students.

METHODS

1. Design and Study Sample

A cross-sectional, descriptive design was used to compare the differences in job search behavior and career distress by different perfectionism types after identifying the perfectionism subtypes of nursing university students. They were sampled using convenience sampling considering the general ratio of male students to female students of about 10%. The ratio of university affiliated hospitals or not was recruited as similarly as possible. The criteria for exclusion were students who had plans to take a semester off or did not intend to get a job immediately after graduation. The participants consisted of 211 third- and fourthgrade undergraduate nursing students, about to graduate, were recruited from three nursing colleges in South Korea from August to September 2016. A total of 220 questionnaires were distributed to nursing students in their classrooms. After discarding nine questionnaires with missing data, 211 questionnaires were used for the analysis. The sample size was estimated using the G*Power 3.1.9 program, with a significance level of 0.05, a medium effect size of 0.15, and a power of 80% for the F test. The minimum sample size was 172. Thus, the sample of 211 nursing students in this study was sufficient to identify significant differences.

2. Instruments

1) Perfectionism

Perfectionism was evaluated using the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R) developed by Slaney et al. [23], after obtaining permission from the developer. It is a self-report questionnaire comprising 23 items across three subscales-High standards, Order, and Discrepancy. “High standards” measures the trait of setting high standards for achievement and performance. “Order” measures preference for neatness and orderliness. “Discrepancy” measures the tendency of respondents to perceive themselves as a failure because they do not meet their standards for performance. Items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). High scores indicate a high tendency for the measured trait. The Cronbach’s ⍺s were .80, .81, and .93 for High standards, Order, and Discrepancy, respectively. The KMO value of Perfectionism was .90, the factor loading and commonality were more than 0.4.

2) Job search behavior

Job search behavior was measured using an instrument after obtaining permission from the developer, which was developed by Kim and Kim [24] is widely used in the Korean population. It is a self-report questionnaire comprising 18 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, measuring preparatory activities to seek job information, and efforts to achieve career goals. Higher scores indicated higher job search behavior. The Cronbach’s ⍺ for this study was .88. The KMO value of Job Search behavior was .80, the factor loading and commonality were more than 0.4.

3) Career distress

Career distress was measured using an instrument developed by Kim and Kang [25] for the Korean population, based on the Cornell Medical Index. CMI is a useful indicator of emotional health [26]. This self-report instrument comprises 22 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, measuring psychological strain for job search and perceived barriers including family financial pressure, academic achievement, and graduate school reputation. Higher scores indicate higher job search stress. The Cronbach’s ⍺ in this study was 0.91. The KMO value of Career distress was .87, the factor loading and commonality were more than 0.4.

3. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the author’s university (7001355-201603-HR-111). The participants were informed of the study purpose and research ethics, including confidentiality and anonymity. The participants understood the purpose of the study and agreed to participate voluntarily. Those who voluntarily provided written informed consent were deemed eligible for the survey. When collecting data, the researcher fully explained the benefits to be expected and the potential risks, as well as the physical and psychological discomfort that may be caused by the survey.

4. Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Korea Data Solution Inc.). Cluster analysis was performed to classify the perfectionism types of nursing students. Two clusters of perfectionists (adaptive, maladaptive) and one cluster of nonperfectionists have emerged in previous research using the Rice et al. [17] APS-R. A two-step cluster analysis proposed by Hair et al. [27] was performed. In the first step, hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method was performed. As a result of examining the change of coefficient in the agglomeration schedule of the first hierarchical clustering analysis, 2~4 clusters were suggested. Among them, when the number of clusters is 3, the number of cases per cluster is appropriate and the conceptual characteristics and interpretive meaning of the clusters are maximized. Therefore, 3 clusters were judged as the optimal number of clusters. In the second stage, the average score of each cluster was added as the initial seed point, and a K-means cluster analysis was performed. The characteristics of each cluster type are shown based on the center point of the final cluster, and the number of clusters was determined by three clusters with a similar number of individuals assigned to each cluster. Cronbach’s ⍺ coefficients were performed to assess reliability of each scale, and factor analysis was performed to confirm the validity. Chi-squared test, analysis of variance, and post-hoc test (Scheffé test) were conducted to examine differences in demographic characteristics, job search behavior, and career distress among the subgroups. To identify the differences in job search behavior and career distress among the subgroups, analysis of covariance, and post-hoc test (Bonferroni’s test) was conducted, controlling for the demographic characteristics that showed significant differences in job search stress and behavior.

RESULTS

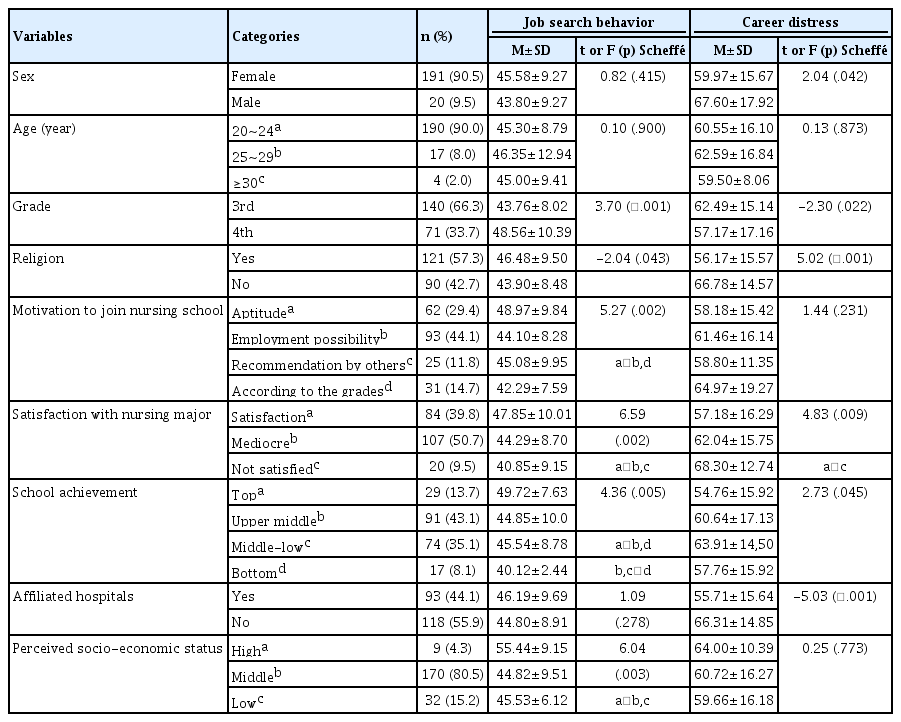

1. Differences in Job Search Behavior and Career

Distress According to Demographic Characteristics Table 1 shows that job search behavior showed significant differences according to grade at school (p<.001), religion (p=.043), motivation for entering nursing school (p=.002), satisfaction with nursing major (p=.002), school achievement (p=.005), and perceived economic status (p=.003). Career distress was significantly different according to gender (p=.042), grade at school (p=.022), religion (p<.001), satisfaction with nursing major (p=.009), school achievement (p=.045), and whether the school had affiliated hospitals (p<001).

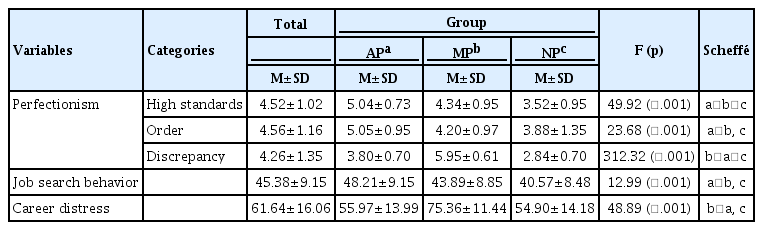

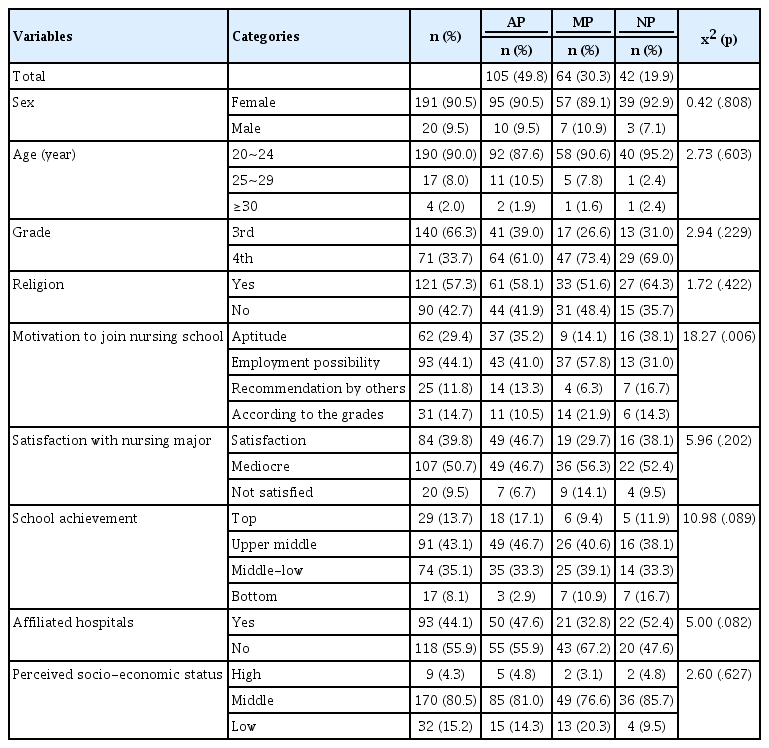

2. Cluster Analysis of the Types of Perfectionism in Nursing Students

The two-step cluster analysis identified three types of perfectionism among nursing students (Tables 2, 3): adaptive perfectionism (AP, 49.8%), maladaptive perfectionism (MP, 30.3%), and non-perfectionism (NP, 19.9%). For the AP group, the M±SD scores were 5.04±0.73 in High Standards, 5.05±0.95 in Order, 3.80±0.70 in Discrepancy. For the MP group, the M±SD scores were 4.34±0.95 in High Standards, 4.20±0.97 in Order, 5.95±0.61 in Discrepancy. For the NP group, the M±SD scores were 3.52±0.95 in High Standards, 3.88±1.35 in Order, 2.84±0.70 in Discrepancy. The difference in High Standards among the AP, MP, and NP groups was significant (F=49.92, p<.001). The Order score in the AP group was significantly higher than that in the MP or NP groups (F=23.68, p<.001). In contrast, the Discrepancy score in the MP group was the highest among the groups (F=312.32, p<.001).

As for the dependent variables, for the AP group, the M±SD scores were 45.38±9.15 in job search behavior, 61.64±16.06 in career distress. For the MP group, the M±SD scores were 43.89±8.85 in Job search behavior, 75.36±11.44 in Career distress. For the NP group, the M±SD scores were 40.57±8.48 in Job search behavior, 54.90±14.18 in Career distress.

3. Group Differences in Job Search Behavior and Career Distress by Perfectionism Type

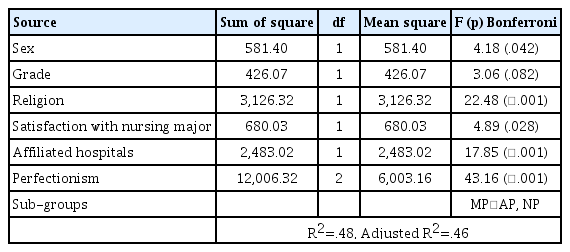

As depicted in Table 4 and 5, as a result of conducting ANCOVA with variables showing significant differences in demographic characteristics as covariates, the post-hoc test showed that job search behavior was significantly higher in the AP and MP groups than in the NP group (F=11.94, p<.001). Career distress in the MP group was significantly higher than that in the AP and NP groups (F=43.16, p<.001).

DISCUSSION

This study compared the differences in job search behavior and career distress according to the perfectionism subtypes of nursing students. The present study identified the perfectionism types of nursing students as clustered into AP, MP, and NP groups. The AP group showed the highest score in the High standard and Order subscales, while the MP group showed the highest score in the Discrepancy subscale. The NP group had the lowest score across all the three subtypes. This is in line with prior cluster analysis studies of a three-class model for perfectionism [24]. Additionally, job search behavior was highest in the NP group, while career distress was highest in the MP group.

This analysis clustered 80% of the participants under perfectionism, including 49.8% in AP and 30.3% in MP. This distribution for perfectionism was significantly higher than the 41.8% reported in a previous study with Chinese university student [22] and 30.3% for U.S. university students [18]. A previous study proposed that a cultural value characterized by competitiveness may foster the drive to be perfect, not only to outperform others, but also to set high standards for their own achievements [17,19]. The Korean culture values competitiveness driven by social success, and this reflects in the educational system and policies. Additionally, as “saving face,” which refers to concealing one’s flaws and presenting oneself as perfect, is typical in Asian cultures, its significant role is observed in the relationship between perfectionism and distress [28]. When they fail to meet other people's expectations, they fear losing their face and tend to become more perfect. A Korean study with non-nursing students reported that 62% were classified into the perfectionism group [29]. Moreover, the future healthcare professionals are being taught that any mistake may be harmful to human life. A high level of perfectionism was shown in other studies with medical students in Korea [22] and dental students in the UK [23]. Perfectionism is more likely to be prescribed by the educational and social contexts of the profession [22]. Sociocultural and educational policies should focus on fostering students’ AP and alleviating MP. MP

In this study, the AP group reported higher job search behavior and lower career distress than the MP group. Similarly, recent studies have reported that individuals with AP have better academic performance [21], high efficacy [16], and positive career-planning attitudes [19]. The AP group in this study reported higher scores for High standards and Order compared with the other groups. However, the AP group’s Discrepancy score was lower than that of the other groups. Individuals with AP set high standards and organize tasks well to achieve goals effectively; thus, they have a relatively low sense of discrepancy between their goals and achievement [16]. Therefore, nursing students with AP are more likely to engage in job search behavior with less career distress than those with MP or NP. These findings provide evidence that individuals with AP, as compared to MP, exhibit better psychological and behavioral functioning with high standards, order, and low discrepancy [29].

Conversely, nursing students with MP in the current study showed the highest career distress among the three groups. This finding supports a large body of studies showing that MP causes a variety of psychological maladjustments, such as stress, burnout, and anxiety [20,21]. In this study, nursing students with MP reported the highest discrepancy among the three groups. The Discrepancy subscale measures the degree of distress experienced when performance does not meet expected standards [23]. A high discrepancy between goals and achievement leads individuals to criticize themselves easily as a failure [19]. Nursing students with MP are likely to devalue their achievements due to their high standards. Even though they actively engage in job search, they perceive discrepancies highly between their present career situation and desirable requirements, which leads to career uncertainty and distress [16]. Kirdok [19] suggested that socially prescribed perfectionism is negatively related to career-planning attitudes. Nursing students with MP within the success-oriented cultural context of Korea face greater career distress from evaluative concerns about the social consequences of their inability to find a good job. This can be a factor lowering the job search behavior of nursing students. Additionally, since job search behavior was self-measured in this study, the cognitive aspect of self-evaluation by nursing students with NP can be reflected in the results. The possibility of measuring worse than the actual job search behavior cannot be ruled out. As much as 15% to 60% of new nurses experience role transition stress-from student to profession-within the first three years of employment [30]. MP is reported as one of the reasons for nurses’ burnout [20], which is related to turnover intention. Considering the high turnover rate and nursing shortage worldwide [1], strategic efforts to mitigate the tendency of MP among nursing students are crucial to reduce career distress and improve adaptive job search behaviors. This can help new nurses complete their education and transition smoothly to practice. Finally, it can help them successfully deal with role transition stress and better adapt to the nursing profession in clinical settings.

Lastly, while nursing students with NP experienced lower career distress than those with MP, their job search behavior was also lower than those with AP and MP in this study. This is possibly explained by the lowest scores in all subcategories of the perfectionism scale. Similarly, Wang et al.[22] found that individuals with NP reported lower scores for high standards compared to those with AP or MP. People with NP are not likely to have high expectations and have less discrepancy between goals and achievement [19]. Moreover, these individuals are not highly motivated to actively pursue their goals [20]. They are emotionally more relaxed but less enthusiastic about taking actions to achieve their goals [22]. The present NP group not only experienced lower career distress but also engaged in less job search behavior compared with the perfectionism group. Sandi [15] suggested that proper stress motivates adaptive actions. Nurse educators should develop specific strategies to motivate students with NP to engage more in job search behavior with productive stress levels. However, studies related to people with NP are limited; therefore, further studies are needed.

The diathesis-stress model [14] proposes that cognitive characteristics differentiate their perceptions of specific situations, leading to different responses. When educators are aware of how the subtypes of perfectionism influence students, they are better able to intervene during career-planning programs [16]. Most studies [13,16,19] of the relationship between perfectionism and career-related problems (i.e., job search behavior and career distress) were conducted with U.S. college students and limited ethnically and culturally diverse samples were included. Little is known about job search behavior and career distress among nursing students according to the type of perfectionism. Thus, this study provides important insights into the area of perfectionism in career-planning programs for nursing students. Especially the results of this study suggest that maladaptive cognitions associated with Maladaptive perfectionism, such as mistake rumination, procrastination, and self-criticism, are associated with career distress. Therefore, cognitive-behavioral approaches can be effective for mental health in nursing students’ career preparation. In particular, as the MP group is vulnerable to career distress, cognitive-behavioral therapy for them should be considered. In addition, In particular, in the case of third-year students who were not satisfied with their major, the career distress was higher while levels of job search behavior were low. These students should be guided to efficiently manage stress and actively prepare for their career path. And it will be necessary to provide a high-quality program that can increase nursing students' major satisfaction in the online educational environment. For example, through virtual simulation education suitable for one's level, student will be able to perform independent nursing and have a sense of satisfaction with the major. The findings also provide nursing educators in academic settings with evidence of interest to support successful transition to practice for new graduate nurses.

1. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, given the small sample size and the use of convenience sampling, caution is needed in generalizing the findings to different populations. Further studies should be conducted using a wider range of larger populations. Second, this study used a self-administered cross-sectional survey, which caused recall bias. Third, the development of perfectionism is due to complicated interactions among personal, parental, and environmental factors [17]. Although the job search stress measured in this study included pressure from family and school factors, a study in which specific familial and environmental factors, such as family structure and communication and socio-economic level, are controlled is needed. Clinical experience in different clinical settings during nursing education also has an impact on career decision-making and planning with regards to preferred professional pathways [6]. The influence of clinical placement and other nursing curricula on career planning should be considered in future research. It is necessary to research whether the job search behavior evaluated by the observation of others differs according to the three groups of perfectionism, as the cognitive aspect perceived by the individual showed a lot of behaviors in the results. Additionally, future research should explore how distress or these behaviors are related to actual employment or professional transition of nursing students.

CONCLUSION

This study identified three clusters of perfectionism among nursing students. Based on these identified types, each group showed differences in job search behavior and career distress. Specifically, nursing university students in the MP group reported high career distress and low job search behavior. Nursing students with NP showed relatively low career distress and low job search behavior. This finding indicates that individual differences in perfectionism affect students’ behavior and emotional responses. Therefore, individualized educational strategies and career-planning programs should be adopted to enhance job search behavior and career distress by alleviating MP and NP tendencies among nursing students. Particularly, interventions to avoid being overwhelmed by fear of failure in one’s career path and irrational beliefs about perfectionism to receive acceptance, as well as cognitive behavioral interventions for cognitive errors, are needed.

Notes

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.