|

|

- Search

| J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs > Volume 33(1); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to investigate how meaning in work influences the connection between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers.

Methods

This study analyzed secondary data. Original data was collected to explore changes in depression, job satisfaction, and quality of life in relation to police officers' psychological trauma. Data were analyzed using the t-test, One-way Analysis of Variance, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, hierarchical regression analysis, and PROCESS macro (version 4.3.1) with the SPSS/27.0 program.

Results

The mean score for wellness was 3.40, meaning in work was 3.49, and job satisfaction was 3.36. The effect size of the mediation was indicated as 0.74, demonstrating that the meaning in work serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers.

Most workers are exposed to various degrees of stress while performing their jobs, and their psychological health is known to affect the outcomes of their work. In particular, when workers have better socio-psychological health, they are more engaged in their work, more satisfied with their job performance, and experience an increase in subjective well-being [1]. The meaning found in work is considered a source of meaning in life as well [2,3], thus greatly impacting an individual's life. From the perspective of positive psychology, positive emotions and meaning are not only complementary dimensions but particularly, the meaning in work is considered a motivational factor in job performance [4,5]. The more significantly a worker perceives the meaning in their work, the higher the sense of autonomy they feel in their job, leading to greater job performance, job satisfaction, mental health, and life satisfaction [4]. Therefore, exploring the meaning in work among workers is very important in predicting job satisfaction.

Police officers work at the forefront of various incidents and crimes, operating in environments that are physically and psychologically threatening [6]. Due to the unique nature of their duties, such as shift work and long working hours, coupled with exposure to life-threatening situations, there is a very high potential for the occurrence of negative factors such as burnout and mental health issues among them [7]. Therefore, the performance of their duties not only affects the job satisfaction and personal health of police officers but also hurts society's safety net and socio-economic costs. However, when individuals perceive their work as meaningful, they tend to invest more effort due to the solid intrinsic motivation associated with the work [8], which improves personal meaning in life and quality, mental health, job satisfaction, and commitment [9]. Furthermore, it tends to reduce negative emotions such as depression and hostility, as well as tendencies for job turnover and the use of sick leave.

Job satisfaction among police officers, just like other workers, influences job performance-related factors such as the degree of job execution, commitment, and intention to leave, but also has a positive effect on the relationship between citizens and police officers [10,11]. An improved relationship with citizens means that police officers better understand and support the community [11], and it can be seen as recognizing that their work is not simply a means to earn income but an act of obtaining understanding for individuals and the surrounding environment and performing greater good. Ultimately, it can be said that police officers who find satisfaction in their work play a positive role in society. However, domestic research focusing on police officers has centered mainly on job satisfaction, and studies exploring how these officers perceive the meaning in their work are rare.

Wellness refers to a state in which the physical, emotional, social, cognitive, and occupational domains are in harmonious balance [12], and the wellness of police officers is deeply related to personal health promotion and quality of life. The wellness of police officers, who are in a unique work environment, is closely related to public safety, and their low level of wellness is associated with decreased work ability and job satisfaction [8]. In other words, the wellness of police officers, prone to imbalance in physical, emotional, social, cognitive, and occupational domains due to shift work, significantly impacts the meaning in work and job satisfaction [5,13]. Due to the nature of the police organization, there is a very lack of literature reported on the mental health of police officers.

According to Duffy et al. [14] meaning in work mediated between calling and job satisfaction. Also, meaning in work significantly affects job satisfaction [15]. Despite the importance of their wellness and the meaning in work in job performance, studies directly exploring the relationship between these variables are scarce. Therefore, this study aims to enhance the understanding of police officers' job performance by identifying their level of wellness, job satisfaction, and the significance of work and examining the relationships between these variables. Moreover, this study aims to elucidate the mediating role of work meaning in the link between wellness and job satisfaction. This study was conducted to provide essential data for psychiatric nursing interventions that can explore more fundamental values and meanings of life, along with addressing psychiatric issues such as identity in the profession of police officers, which are directly linked to public safety.

This study, which analyzed secondary data, sought to confirm the mediating role of meaning in work within the correlation between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers (In preparation). The original data comes from the cohort study on Police’s Health and Job Satisfaction, which is a prospective longitudinal study designed to identify factors that influence depression, job satisfaction, and quality of life to the psychological trauma experiences and related variables among police officers. The purpose of the cohort study is to observe the trends by year in depression, job satisfaction, and quality of life related to the psychological trauma of police officers. No studies have been published using the same variables utilized in this research. IRB approval was obtained from the C University after reporting the intention to conduct a regression analysis study on job satisfaction influencing factors using the collected original data.

The participants of this study are 799 police officers who agreed to use their personal information during the job training course for police officers in 2019 and participated in the follow-up survey out of the original 1,083. To determine the requisite sample size for this study, we employed G*power 3.197 [16]. The calculation was based on the parameters necessary for multiple regression analysis. We set a medium effect size of .25, in line with the standard for multiple regression, a significance level of .05, a power of .95, and two independent variables (wellness and meaning in work). Based on these parameters, the required sample size was 252.

All instruments used in this study were adapted into Korean and validated. Permission for their use was obtained via email from the developers of the instruments and the researchers who adapted them into the Korean versions.

Wellness was measured using the Wellness Index for Workers (WIW), which was developed by Choi et al. [12] for South Korean workers. This instrument consists of 18 items and is organized into five sub-factors: physical, emotional, social, cognitive, and occupational wellness. It uses a 5-point Likert scale where each item is scored as 1=not at all, 2=mostly not, 3=moderate, 4=mostly, and 5=very much, with higher scores indicating higher levels of wellness. At the time of the tool's development, Cronbach’s ⍺ was .91; for this study, it was .95.

Job satisfaction was measured using the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), developed by Weiss et al. [17], and adapted into Korean by Park [18]. This tool consists of 20 items and is divided into three sub-factors: intrinsic satisfaction, extrinsic satisfaction, and general satisfaction. It employs a 5-point Likert scale, with ratings of 1=very dissatisfied, 2=dissatisfied, 3=neutral, 4=satisfied, and 5=very satisfied; where higher scores indicate a higher degree of job satisfaction. In Park’s study [18], Cronbach’s ⍺ for the sub-variables was above 0.79, and in this study, it was .96.

The meaning in work was measured using the Korean Version of the Working As Meaning Inventory, developed by Steger et al. [4] and validated by Choi and Lee [5]. The scale includes a total of 10 items, covering three sub-factors: positive meaning in work, making meaning through work, and motivation for the greater good. This tool uses a 5-point Likert scale, where 1=not at all, 2=mostly not, 3=average, 4=mostly, and 5=very much so; thus, higher scores indicate a greater sense of meaning in work. Choi and Lee [5] reported a Cronbach’s ⍺ of .91, and in this research, the Cronbach’s ⍺ was .95.

The general characteristics of the participants included six items: age, gender, shift work, marital status, hobbies, and department of work. The classification of the department of work is as follows. Participants responsible for community policing stations, district offices, traffic, and public safety were categorized as patrol officers, while those handling investigations and criminal cases, including domestic violence and sexual violence against women or youth, were categorized as detectives. Those in charge of foreign affairs or security-related tasks were classified as others.

This study collected data through an online survey targeting police officers who participated in the job training course for police officers in the second half of 2019 and who agreed to a follow-up survey. The original data collection period was from October 25, 2020, to February 8, 2021. The link to the Google online survey was sent to the participants via the KakaoTalk business channel. Before participating in the survey, they were provided with an explanatory document detailing the purpose of the study, confidentiality, and voluntary participation. The data collection process commenced with individuals who willingly consented to participate in the study. Although 806 individuals participated in the survey, after excluding 7 respondents who duplicated their responses, a total of 799 were used for analysis. To collect the original data, IRB approval (1041566-202009-HR-003-01) was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of C University.

The collected data were coded and analyzed using IBM SPSS 27.0 and PROCESS macro (Version 4.3.1). To assess the variations in general characteristics and job satisfaction, independent sample t-tests and One-way ANOVA were utilized. The relationships between the participants' wellness, meaning in work, and job satisfaction were analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The statistical significance was assessed using threshold where the p-value was set at less than .05. Before verifying the mediating effect, covariates related to job satisfaction among general characteristics were controlled, and the effect of wellness on job satisfaction was verified using hierarchical regression analysis. The mediating effect of meaning in work between wellness and job satisfaction was tested using the PROCESS Macro Model in regression analysis by the simultaneous input method proposed by Hayes [19]. The significance of the mediating effect was analyzed by extracting 5,000 bootstrap samples and examining the 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Bootstrapping is a method that reduces errors that may occur in traditional tests such as Sobel's test. It is advantageous as it does not require a large number of samples and does not demand the assumption of independence of path coefficients, making it increasingly used for validating mediating effects.

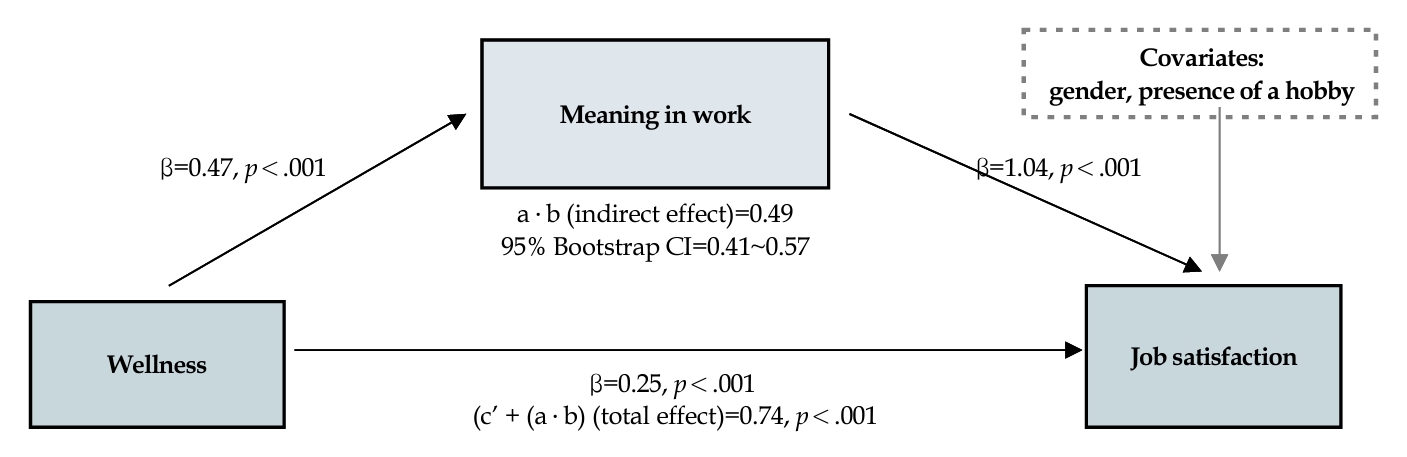

The mediational model used in this study is shown in Figure 1. The term ‘a’ denotes the unstandardized regression coefficient that characterized the connection between wellness and the meaning of work, taking into account the control for covariates. The term ‘b’ is the unstandardized regression coefficient for the relationship between the meaning in work and job satisfaction, also after controlling for covariates, and the direct effect ‘c’ is the unstandardized regression coefficient for the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction after controlling for covariates. The term ‘a ․ b’ represents the indirect effect (mediation effect) of the meaning in work on the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction, and ‘c’ is the total effect on job satisfaction, which is ‘c +(a ․ b)’. Additionally, to examine the effect size of the mediation, the ratio of the indirect effect to the direct effect was calculated.

The average age of the participants was 32.60±8.53 years, and the majority, 56.8%, were working in police boxes, precincts, traffic, public safety, and mobile units. Males comprised 79.8% of the sample, and 73.0% were shift workers. Those without a spouse made up 77.9%, and 36.9% reported having a hobby. Differences in job satisfaction according to general characteristics were significant by gender (t=2.40, p=.017) and the presence of a hobby (t=6.31, p<.001). However, there were no significant differences by age (F=0.19, p=.822), work department (F=1.36, p=.256), shift work (t=-0.55, p=.585), or having spouse (t=-0.98, p=.330) as shown in Table 1.

The results concerning the wellness of the study participants, the meaning in their work, and the level of job satisfaction are as presented in Table 2. The average score for wellness was 3.40±0.68, with social wellness scoring higher at 3.83±0.70, and physical wellness at 3.07±0.86. The average score for the meaning in work was 3.49±0.76, with motivation for a greater good scoring the highest at 3.53±0.78. The average job satisfaction score was 3.36± 0.69, with extrinsic satisfaction at 3.08±0.82, intrinsic satisfaction at 3.57±0.68, and general satisfaction at 3.30±0.77.

Before conducting hierarchical regression analysis, it was verified whether the conditions for regression analysis were met. The Durbin-Watson value was 1.93, close to 2, confirming the independence of the residuals. The tolerance limit was 0.49, and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was 2.03, satisfying the conditions for autocorrelation among variables and multicollinearity. In the hierarchical regression analysis, gender and the presence of a hobby, which showed differences in job satisfaction among general characteristics, were included (Step 1: F=19.29 (p<.001), R2=0.05). As a result of introducing wellness in the next step, the regression model was significant (Step 2: F=449.45 (p<.001), R2=0.41, R2 change=0.36 (p<.001)), and it was shown that job satisfaction increases as wellness increases (Table 3).

The results of the analysis, controlling for covariates (gender, presence of a hobby), on whether the meaning of work mediates the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction are as follows. In the analysis where wellness was independent variable and job satisfaction the dependent variable, a significant positive correlation was observed (a=0.47, p<.001). In other words, the higher the level of wellness, the greater the perceived meaning in work. Next, when job satisfaction was analyzed as the dependent variable, with wellness and the meaning in work as predictive variables, a significant positive relationship was found between the meaning in work and job satisfaction (b=1.04, p<.001). Additionally, the direct effect of wellness on job satisfaction also showed a significant positive relationship (c’=0.25, p<.001). The indirect effect (mediation effect) of wellness on job satisfaction through the meaning in work was also significant (a ․ b=0.47×1.03=0.49, 95% Bootstrap CI [0.41~0.57]). This indicates that the direct influence of wellness on job satisfaction was significant, and the indirect impact via the meaning in work was also significant. This suggests that the meaning in work services as a partial mediator in the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction. The effect size of this mediation was indicated as 0.74 (Figure 1, Table 4).

The objective of this research was to confirm the role of work meaning as a mediator in the link between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers, with the goal of offering psychiatric nursing interventions to enhance job satisfaction within this group.

First, the wellness score of the study participants was found to be 3.40. Although it is difficult to make a direct comparison due to the absence of studies conducted on the same occupational group, the average wellness score of workers in a large-scale workplace was 3.46[20], and the wellness score of firefighters was 3.72[21], which is higher than the results of this study's participants. Among the sub-factors, social wellness showed the highest score, which seems to reflect the efforts of police officers to communicate to contribute to the improvement of the local community [22] and shows that their peers accept them and have secured a network within relatively well-structured organizational systems. On the other hand, the score for physical wellness was found to be the lowest. Similar results were reported in a study [21] that found social wellness to be the highest and physical wellness to be the lowest among workers, which supports the results of this study. This shows that it is not easy for police officers who work shifts and long hours to maintain appropriate weight through regular exercise and a balanced diet while performing their job. It also appears to reflect the occupational characteristics of having both major and minor injuries due to extensive physical use. Health issues among workers can lead to adverse outcomes such as reduced work capacity, productivity loss, and personal problems [1]. It seems necessary to develop psychiatric nursing interventions that can enhance the physical and psychological wellness of police officers, who have a socially important role, and it is necessary to prepare intervention measures for them.

In this study, the mean score of meaning in work was 3.49. While direct comparisons with the same profession are challenging due to the lack of similar studies, research with nurses—who have a similar work structure—showed scores of 3.05 [23] and 3.57 [24], indicating that the participants in this study had either higher or lower scores. Notably, among the sub-factors, the motivation for contributing to a greater good scored the highest, which seems to reflect the police officers' characteristic desire to create a brighter and more positive society. Conversely, finding positive meaning in their work scored the lowest, which may indicate a discrepancy between expectations and the rewards or fulfillment derived from their work. The perception of meaning at work is crucial as it relates to the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, which enhances life satisfaction and contributes to organizational retention [24]. Therefore, efforts are needed to find strategies that enhance the meaning of police officers' work and to implement methods using psychiatric nursing interventions.

The job satisfaction score was 3.36 on average, which is somewhat higher compared to a similar study on nurses working in shift patterns at university hospitals, where the average job satisfaction score was 3.10 [23]. Although it is difficult to find studies using the same instrument specifically on police officers, this comparison with nurses suggests that police officers might experience a higher job satisfaction. The most potent predictive variable for job satisfaction among police officers was stress [25,26], indicating that as work-related pressure and frustration increase, so does the likelihood of job dissatisfaction. This study's participants mainly showed high intrinsic satisfaction, which is a high level of satisfaction derived from the work itself. However, extrinsic satisfaction was the lowest, which may reflect the finding that the more police officers are satisfied with their job, the more they believe their work is meaningful and involves helping others and collaborating with people [26]. The results of job satisfaction and its sub-variables in this study were similar to those related to the sense of meaning in work. Job satisfaction is an essential factor that enables workers to be more engaged in their work, underscoring the need to develop intervention programs to enhance job satisfaction among police officers. Moreover, job satisfaction has a positive impact not only on workplace attitudes and performance but also on an individual's life [27], suggesting that consideration should be given to enhancing the wellness of police officers to improve their job satisfaction. The nature of police work being exposed to severe stress, such as post-traumatic stress, could be a differentiating factor from other occupations [28]. Given the results of this study, it can be suggested that to improve the job satisfaction of police officers, it is necessary to develop a psychiatric nursing intervention that enhances their overall wellness.

Lastly, the meaning in work showed a partial mediating effect between wellness and job satisfaction. This aligns with research findings [9] that suggest an improvement in the meaning in life and quality of life, as well as mental health, enhances job satisfaction and dedication. The more a worker finds their work meaningful, the higher they perceive autonomy in their duties, which improves job performance and job satisfaction and increases life satisfaction [4]. Although it has been proven that the meaning in work is an essential element for workers, these previous studies looked at the meaning in work as a mediating effect within the same occupation were hard to find. However, it was evident that, similar to studies involving general employees, the meaning in work is a mediator in job satisfaction [14]. Therefore, it would be possible to maximize job satisfaction for police officers by not only implementing psychiatric nursing interventions that enhance wellness but also by incorporating elements that strengthen the meaning in work in such programs.

The significance of this study is as follows. First, this study can help understand the mental health of occupational groups that have irregular working hours, unpredictable tasks, and exposure to various incidents. Second, by confirming the partial mediating effect of the meaning in work on the relationship between police officers' wellness and job satisfaction, it has provided ideas for developing psychiatric nursing interventions to improve their job satisfaction. However, despite the significance of this research, it has the following limitations. Firstly, since the subjects of this study are limited to those participating in job training programs, there may be difficulties in generalizing the results. Therefore, further research is needed that examines differences in job and rank among police officers in various regions. Secondly, since this study targets a small number of police officers, the interpretation of this result needs to be cautious. Therefore, it is thought that subsequent research should consider job-related variables that may affect the wellness and job satisfaction of police officers.

The results of this study indicated that wellness is a factor that influences the meaning in work, and the meaning in work, in turn, affects job satisfaction. Furthermore, the meaning in work mediates the path through which wellness impacts job satisfaction. To enhance job satisfaction among police officers, it is necessary to promote wellness and develop psychiatric nursing interventions that can help find meaning in work and apply it through various strategies. Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations are proposed. Firstly, additional studies are required to explore the mediating role of meaning in work within the context of the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers who are stationed in diverse regions and perform a variety of tasks. Secondly, as the meaning in work has been shown to mediate the relationship between wellness and job satisfaction among police officers, there is a need for the development and subsequent validation of psychiatric nursing intervention to enhance the meaning of work to improve their wellness and job satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kim, SH at the National Police Agency for supporting the collection.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Kang, Kyonghwa has been an editorial board member since January 2020, but has no role in the decision to publish this article. Except for that, no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

The purpose of the original data collection is to observe the trends by year in depression, job satisfaction, and quality of life related to the psychological trauma of police officers. This secondary data analysis study used raw data to verify the research topic of identifying variables that affect job satisfaction. Studies using the same variables utilized in this study have not been published and will not be published.

Notes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization or/and Methodology: Han, S & Kang, K

Data curation or/and Analysis: Kang, K

Funding acquisition: Kang, K

Investigation: Han, S & Kang, K

Project administration or/and Supervision: Kang, K

Resources or/and Software: Kang, K

Validation: Kang, K

Visualization: Han, S & Kang, K

Writing: original draft or/and review & editing: Han, S & Kang, K

Table 1.

Job Satisfaction according to General Characteristics (N=799)

Table 2.

Level of Wellness, Meaning in Work, and Job Satisfaction (N=799)

Table 3.

The Relationship of Wellness on Job Satisfaction (N=799)

| Variables |

Step I |

Step II |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 61.36 | 1.22 | 50.32 | <.001 | 21.34 | 2.16 | 9.90 | <.001 | ||

| Gender† | 2.26 | 1.22 | .07 | 1.85 | .065 | 0.37 | 0.97 | .01 | 0.39 | .700 |

| Presence of a hobby‡ | 6.07 | 1.06 | .21 | 5.71 | <.001 | -0.07 | 0.89 | -.00 | -0.08 | .940 |

| Wellness | 0.74 | 0.04 | .64 | 20.74 | <.001 | |||||

| F=19.29 (<.001), R2=0.05 | F=449.45 (<.001), R2=0.41 | |||||||||

| F change=430.16 (<.001), ΔR2=0.36 (<.001) | ||||||||||

Table 4.

Model Coefficients for a Simple Mediation Analysis with Covariates (N=799)

| Variables |

Consequent variables |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Meaning in work |

Job satisfaction |

|||||||||

| Coeff. | SE | t (p) | Bootstrap 95% CI | Coeff. | SE | t (p) | Bootstrap 95% CI | |||

| (Constant) | 5.10 | 1.52 | 3.35 (.001) | 16.81 | 2.73 | 6.15 (<.001) | ||||

| Gender† | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.68 (.494) | -0.81 | 0.84 | -0.98 (.329) | ||||

| Presence of a hobby‡ | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.82 (.413) | -0.30 | 0.77 | -0.38 (.705) | ||||

| Wellness | a | 0.47 | 0.02 | 27.27 (<.001) | 0.44~0.51 | c’ | 0.25 | 0.04 | 5.69 (<.001) | 0.16~0.34 |

| Meaning in work | b | 1.04 | 0.07 | 15.55 (<.001) | 0.36~0.48 | |||||

| R2=.54, F=275.74, p<.001 | R2=0.56, F=224.89, p<.001 | |||||||||

REFERENCES

1. Ha YJ. Strength of the power I lead. 1st ed. Seoul: Tornado Media Group; 2016. p. 30-32.

2. Ardichvili A, Kuchinke KP. International perspectives on the meanings of work and working: current research and theory. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2009;11(2):155-167.https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422309333494

3. Michaelson C, Pratt MG, Grant AM, Dunn CP. Meaningful work: connecting business ethics and organization studies. Journal of Business Ethics. 2014;121(1):77-90.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1675-5

4. Steger MF, Dik BJ, Duffy RD. Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment. 2012;20(3):322-337.https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

5. Choi H, Lee JM. Validation of Korean version of working as meaning inventory. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology. 2017;31(4):1-25.https://doi.org/10.21193/kjspp.2017.31.4.001

6. Purba A, Demou E. The relationship between organizational stressor and mental wellbeing within police officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19: 1286 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7609-0

7. Youn BH, Song BG. Study on the effect of police officers' awareness of work-life balance on job satisfaction: mediation effects of intrinsic motivation. Korean Police Studies Review. 2014;13(1):91-116.

8. Steger MF, Dik BJ. Work as meaning: individual and organizational benefits of engaging in meaningful work In: Linley P. A, Harrington S, Page N, editors. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 131-142.

9. Mujah W, Ruziana R, Samad A, Singh H, D'Cruz OT. Meaning of work and employee motivation. Terengganu International Management and Business Journal. 2011;1(2):18-26.

10. Kang W, Nall MK. Perceived citizen cooperation, police operational philosophy, and job satisfaction on support for civilian oversight of the police in South Korea. Asian Journal of Criminology. 2011;6: 177-189.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-011-9116-9

11. Wycoff MA, Skogan WG. The effects of a community policing management style on officers' attitudes. Crime & Deliquency. 1994;40(3):371-383.https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128794040003005

12. Choi MJ, Son CS, Kim J, Ha Y. Development of a wellness index for workers. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2016;46(1):69-78.https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2016.46.1.69

13. Blustein DL. The role of work in psychological health and wellbeing: a conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. American Psychologist. 2008;63(4):228-240.https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.4.228

14. Duffy RD, Bott EM, Allan BA, Torrey CL, Dik BJ. Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(1):50-59.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026129

15. Negri L, Cilia S, Falautano M, Grobberio M, Niccolai C, Pattini M, et al. Job satisfaction among physicians and nurses involved in the management of multiple sclerosis: the role of happiness and meaning at work. Neurological Sciences. 2022;43: 1903-1910.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05520-8

16. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1149-1160.https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

17. Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation. 1967;22: 120

18. Park IJ. Validation study of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) [master's thesis]. [Seoul]: Seoul National University; 2005. p. 75-77.

19. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach 2nd ed New York, NY: Guilford; 2018 77-86.

20. Ha YM, Yang SK. The influence of worker's exercise self-efficacy, self-determination, exercise behavior on wellness: focusing large-scale workplace workers. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2019;17(2):207-216.https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2019.17.2.207

21. Kang MA, Ha YM, Chae YJ. The influence of fire officials' job stress on wellness: a mediating effects of positive psychological capital. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2021;19(5):333-342.https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2021.19.5.333

22. Choi MJ, Lee DH, Kang WS, Ha YM, Kim SH. Impacts of wellness components on individuals' wellness status for wellness convergence systems. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2015;13(7):381-391.https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2015.13.7.381

23. Han S. The development and evaluation of logotherapy-based work meaning program for nurses [dissertation]. [Seoul]: Seoul National University; 2019. p. 52

24. Park JY, Woo CH. The effect of job stress, meaning of work, and calling on job embeddedness of nurses in general hospitals. Journal of the Korea Convergence and Society. 2018;9(7):105-115.https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2018.9.7.105

25. Alexopoulos EC, Palatsidi V, Tigani X, Darviri C. Exploring stress levels, job satisfaction, and quality of life in a sample of police officers in Greece. Safety and Health at Work. 2014;5(4):210-215.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2014.07.004

26. Paoline EA, Gau JM. An empirical assessment of the sources of police job satisfaction. Police Quarterly. 2020;23(1):55-81.https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611119875117

27. Fourie M, Deacon E. Meaning in work of secondary school teachers: a qualitative study. South African Journal of Education. 2015;35(3):1-8.https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v35n3a1047